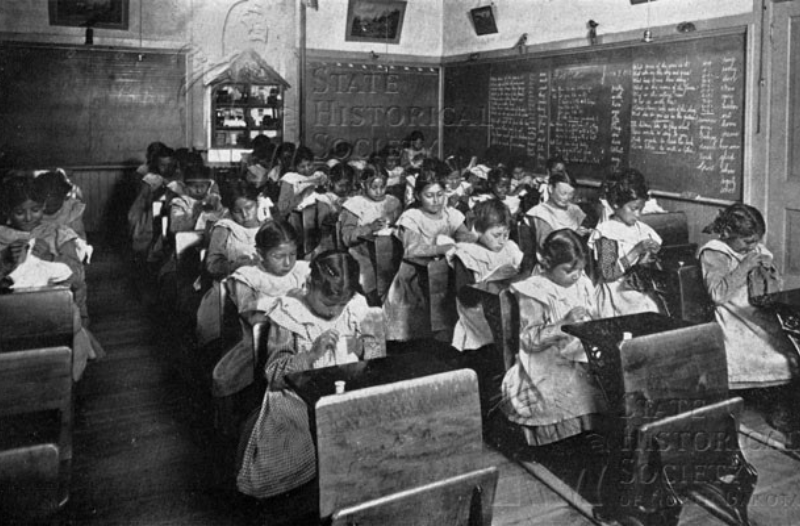

Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart describes historical trauma as “…the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over one’s lifetime and from generation to generation following loss of lives, land and vital aspects of culture.” The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief.

Impact of Boarding Schools [1]

- Individuals

- Loss of identity

- Low self esteem

- No sense of safety

- Institutionalized

- Difficulty forming healthy relationships

- Families

- Loss of parental power

- Near destruction of extended family system

- Tribal Communities

- Loss of sense of community

- Loss of language

- Loss of tribal traditions and ceremonies

- Tribal Nations

- Weakened nations structure

- Depleted numbers for enrollment

2014 Native Youth Report

The 2014 White House Report on Native Youth[2] lists major disparities in health, education, as well as a state of emergency regarding Native youth suicide and PTSD rates three times the general public—the same rate as Iraqi war veterans.

Unfortunately, in addition to the other negative effects of decades of debilitating poverty on Native youth, educational progress was and continues to be hindered by poor physical infrastructure in the schools serving Native youth. Today, federal and state partners are making improvements in a number of areas, including education, but absent a significant increase in financial and political investment, the path forward is uncertain. Despite advances in tribal self-determination, the opportunity gaps remain startling:

- More than one in three American Indian and Alaska Native children live in poverty

- The American Indian/Alaskan Native high school graduation rate is 67 percent, the lowest of any racial/ethnic demographic group across all schools. And the most recent Department of Education data indicate that the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) schools fare even worse, with a graduation rate of 53 percent, compared to a national average of 80 percent.

- Suicide is the second leading cause of death—2.5 times the national rate—for Native youth in the 15 to 24 year old age group.

In 1969, the Senate convened a Special Subcommittee on Indian Education to investigate the challenges facing Native students. The resulting report, entitled “Indian Education: A National Tragedy, a National Challenge,” informally known as the Kennedy Report, delivered a scathing indictment of the federal government’s Indian education policies. It concluded that the “dominant policy . . . of coercive assimilation” has had “disastrous effects on the education of Indian children.” The Subcommittee detailed 60 recommendations for overhauling the system, all of which centered on “increased Indian participation and control of their own education programs.” Congress also moved to enhance the role of Native nations in education, with the Indian Education Act of 1972, the landmark Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, the Tribally Controlled Community College Assistance Act of 1978, and the Tribally Controlled Schools Act of 1988. These laws provided tribal governments, communities, and families with unprecedented opportunities to influence the direction of their children’s future.

[1] Sandy White Hawk, First Nations Repatriation Institute and NABS Board of Directors[2] https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/20141129nativeyouthreport_final.pdf