Recently, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition published the second edition of Healing Voices Volume 1, which is authored by our CEO, Christine Diindiisi McCleave. The following is an excerpt from this very important and informative publication:

A SYSTEM OF DOMINATION

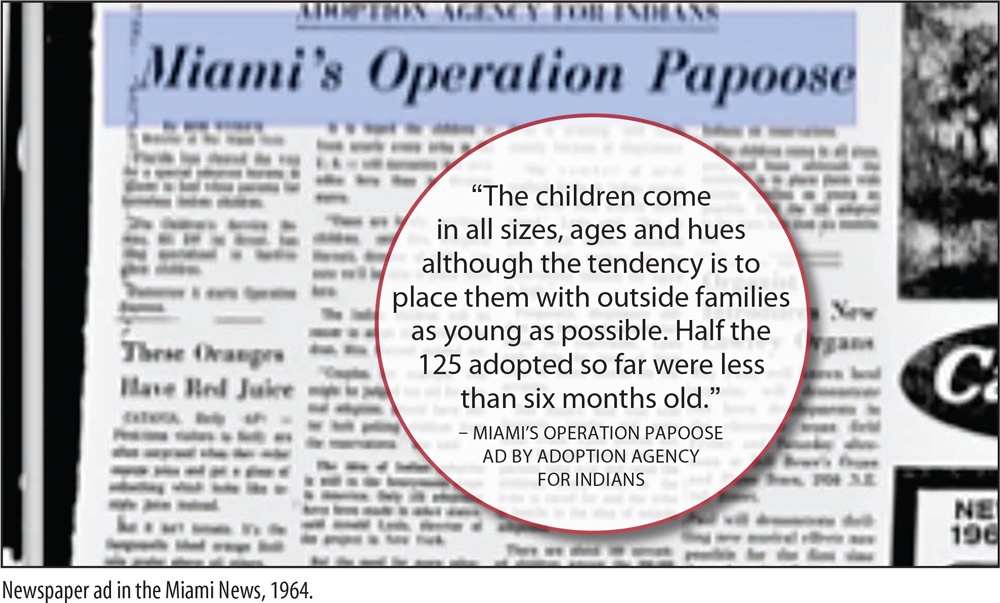

In 1958, as Indian boarding schools were starting to wane, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) created the Indian Adoption Project.

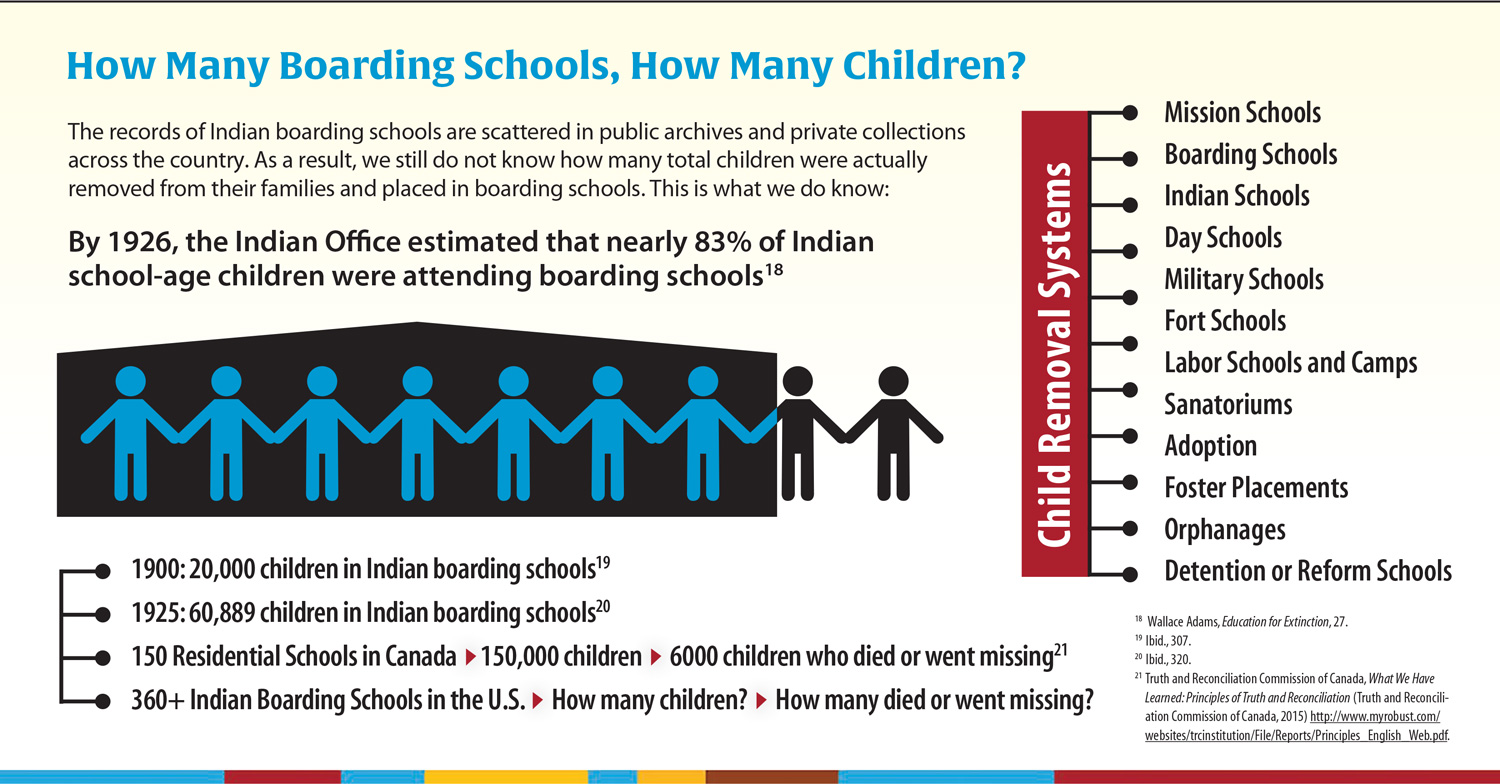

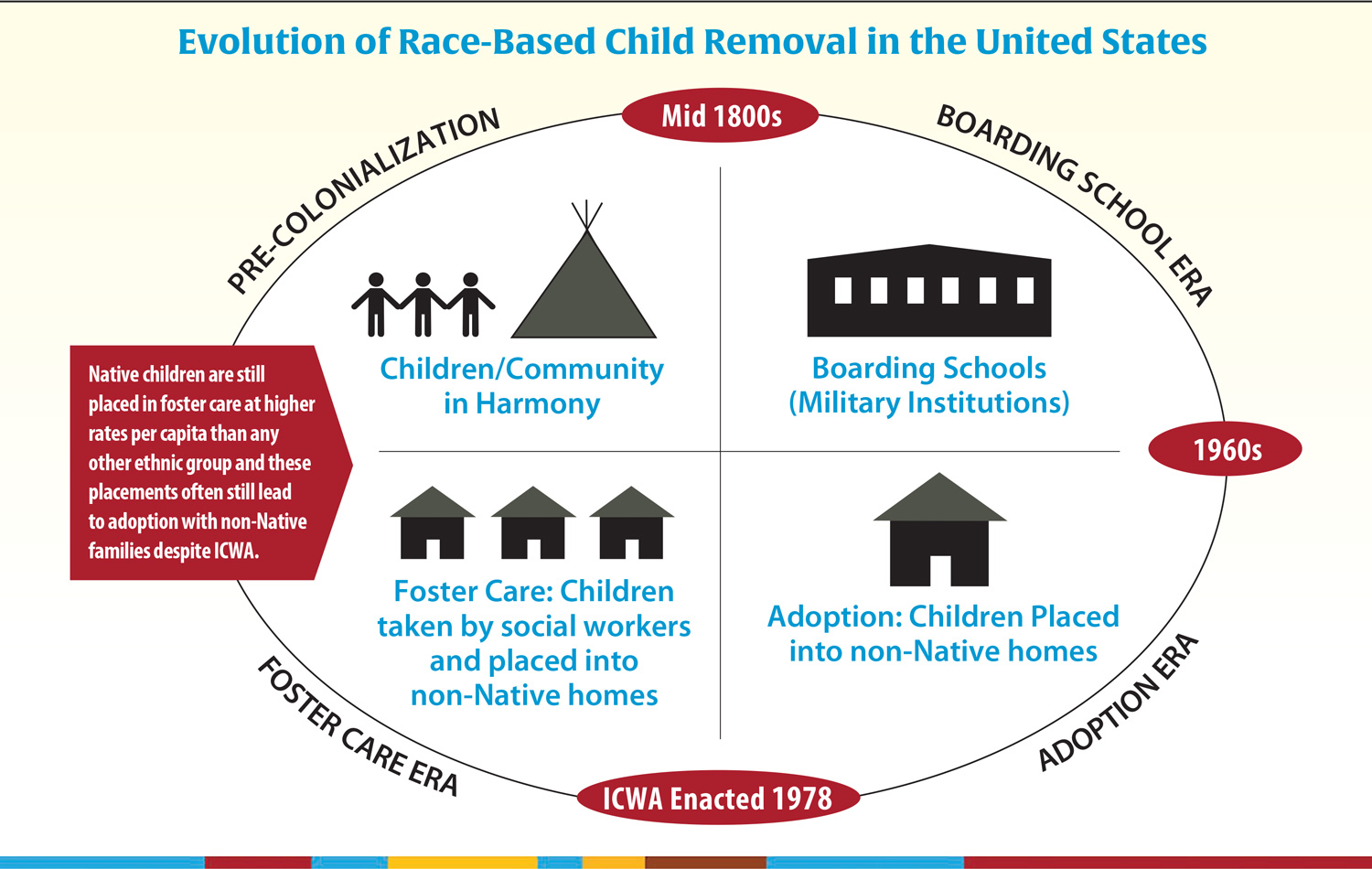

Both the U.S. Indian Boarding School and the Indian Adoption policies were intentionally designed to force assimilation and eradicate Native cultures and family systems.

“This was not an accident of history, it was a government program designed to save the government money and dismantle Tribal Nations. All under the guise of integrating Native children more fully into American society,” said Melissa Olson (Ojibwe) in a documentary she produced exploring the cultural and historical impacts of forced adoption.13

When the BIA started the project it enlisted social workers to visit reservations and convince parents to sign away their parental rights. It was a way to assimilate these children into “civilization,” Olson said. The government believed adoption was the best option for dealing with the perennial “Indian problem.”14

“When you removed a child and put them in a non-Indian family, they wouldn’t be getting to know other Indian people as they would in a boarding school, they would hopefully be raised in a middle-class family. And so the idea was that they would be fully assimilated, and at no cost to the government,” said MargaretJacobs, non-Native author of “A Generation Removed,” a book on forced Indian adoption.15

Sandy White Hawk (Lakota), NABS Board President and Executive Director for the First Nations Repatriation Institute, writes about her experiences as an adoptee. As a part of her writing, White Hawk frequently looks to the connections between boarding school policy and adoption of Indigenous children to non-Indigenous families.

“This idea did not come from grace (a basic Christian concept), but rather a cruel assumption that Indian families did not have a religion and a spiritual belief system or a family system. All they saw was poverty and alcoholism-circumstances we came upon due to colonization-and they compared it to their life and concluded that they and their way of life were superior,” writes White Hawk.16

This notion of white supremacy created an abusive environment where White Hawk was forcibly separated from her traditional natural spirit. She writes, “My adoptive mother constantly reminded me that no matter what I did, I came from a pagan race whose only hope for redemption was to assimilate to white culture. From the time I was small I heard things like, ‘you better not grow up to be a good for nothing Indian,’ and so it was a continuation of identity shaming and cultural genocide,” said White Hawk.17

By the 1960s about one in four Native children were living apart from their families. Many of these adopted children, now adults, struggle with memories from traumatic childhoods in abusive homes, while trying to figure out where they fit in as Natives in white communities.

In 1978, the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was created to stop these adoptions that deliberately removed children from Tribal communities, but the struggle continues.

Native children are still placed in foster care at higher rates per capita than any other ethnic group, effectively removing them from their communities. These placements often still lead to adoption with non-Native families, despite ICWA.

“These problems aren’t going to be resolved until people are educated enough to change the model. We are still dealing with ongoing removal of our children-from boarding schools, to adoption, to foster care and other institutions. This all started from the Boarding School Era when it was okay to ‘Kill the Indian to Save the Man.'” said, Christine Diindiisi McCleave (Ojibwe), NABS Executive Director. “Today, the government is still taking our children. It’s race-based systematic removal of children, which is ongoing cultural genocide.”

2014 NATIVE YOUTH REPORT

The 2014 White House Report on Native Youth lists major disparities in health and education, and declares a state of emergency regarding Native youth suicide and PTSD rates, which are three times the general public-the same rate as veterans of the Iraqi war.22

Unfortunately, in addition to the other negative effects of decades of debilitating poverty, educational progress was and continues to be hindered by poor physical infrastructure in the schools serving Native youth. Today, federal and state partners are making improvements in a number of areas, including education, but absent a significant increase in financial and political investment, the path forward is uncertain. Despite advances in Tribal self-determination, the opportunity gaps remain startling:

- More than one in three American Indian and Alaska Native children live in poverty.23

- The American Indian/Alaska Native high school graduation rate is 67 percent, the lowest of any racial/ethnic demographic group across all schools.24 The most recent Department of Education data indicate that the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) schools fare even worse, with a graduation rate of 53 percent, compared to a national average of 80 percent.25

- Suicide is the second leading cause of death-2.5 times the national rate-for Native youth in the 15 to 24 year old age group.26

In 1969, the Senate convened a Special Subcommittee on Indian Education to investigate the challenges facing Native students. The resulting report, titled “Indian Education: A National Tragedy, a National Challenge,” informally known as the “Kennedy Report,” delivered a scathing indictment of the federal government’s Indian education policies.27 It concluded that the “dominant policy…of coercive assimilation” has had “disastrous effects on the education of Indian children.” The Subcommittee detailed 60 recommendations for overhauling the system, all of which centered on “increased Indian participation and control of their own education programs.” Congress also moved to enhance the role of Native nations in education, with the Indian Education Act of 1972, the landmark Indian Self-determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, the Tribally Controlled Community College Assistance Act of 1978, and the Tribally Controlled Schools Act of 1988. These laws provided tribal governments, communities, and families with unprecedented opportunities to influence the direction of their children’s future. Indian education has made much progress in the self-determination era, but acknowledgement and awareness of the boarding school legacy is needed to create a paradigm change.

Download the full Healing Voices Volume 1 here.