The U.S. Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs—which oversees the Bureau of Indian Education—announced last month plans for reopening the 187 schools within their oversight “to the maximum extent possible” by a September 16 deadline. The plan includes reopening directives for the 55 Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) operated schools and reopening guidance for the 132 Tribally controlled schools.1 With the reopening date looming closer, many communities have demonstrated strong resistance to the federal order, urging the Department of the Interior to reverse the directives to resume in-person schooling.2

In a recent article published by Indian Country Today, Mary Annette Pember (Red Cliff Ojibwe) documented widespread objection from community members to BIE directives compelling students return to in-person schooling amid the COVID-19 global pandemic.3 Citing the fact that the Navajo Nation has been one of the worst hotspots affected by the pandemic, including the lack of capacity of the IHS to handle outbreaks, and reports that the virus has disproportionately impacted Indigenous people at nearly twice the rate of non-Natives, Tribal communities continue to express justifiable concerns regarding the health hazards that the BIE reopening plans present.

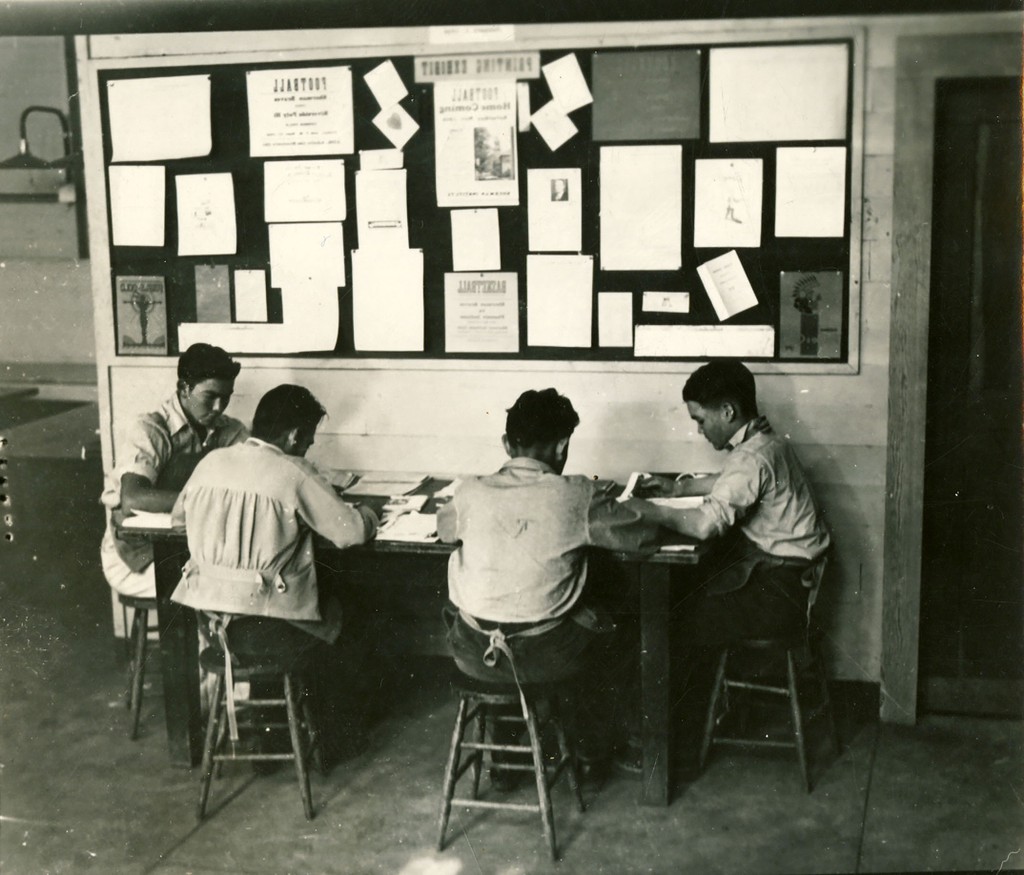

These factors would seem to be reason enough to pressure the federal government to heed the concerns of Tribal communities across the country. Yet, with the present administration’s unrelenting fervor to reopen schools despite the risk to public health, a historical amnesia demonstrated by the U.S. regarding the Indian boarding school era, and the role that infectious diseases have played in this expression of assimilation policy, the roots to this tension run deep. Epidemics of grave proportion plagued boarding school institutions from the very beginning. Outbreaks of tuberculosis, trachoma, measles, pneumonia, mumps, and influenza were all too frequent in these institutions that subjected children to poorly ventilated and unhygienic living quarters, chronic malnutrition, corporal punishment, abuse, and forced labor.4

Disease and death were so common that most off-reservation boarding schools had their own graveyard, and at times compelled school carpenters to construct coffins for students.5 In 1916, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Cato Sells, offered a telling insight into the role of disease to the boarding school experience by stating, “We cannot solve the Indian problem without Indians. We cannot educate their children unless they are kept alive.”6 The Meriam report of 1928—the first congressionally commissioned investigation of the U.S. governments’ boarding school project—revealed the many cases of tragic abuse and neglect of Native youth under federal oversight.7 Despite the report’s many recommendations to address the disease, death, and abuse in Indian boarding schools, the federal government was slow to make meaningful changes.

The intergenerational trauma that has been subjected to Native communities as a result of the Indian boarding school legacy continues to reveal itself in many ways to this day. Resistance to federal orders to return to in-person schooling amid a global pandemic evokes a painful and visceral historical memory that must be considered in the preparations for the education of our Indigenous relatives throughout Turtle Island. Neglecting this truth furthers the trauma that was embedded in the assimilation efforts established by the federal Indian boarding school policy.

Samuel B. Torres, ED.D.Director of Research and Programs

(Bio)

1 https://www.bie.edu/schools/directory

4 David W. Adams, Education for Extinction, 1995

5 David W. Adams, Education for Extinction, 1995

6 Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1916

7 Lewis Meriam et al., The Problem of Indian Administration, 1928