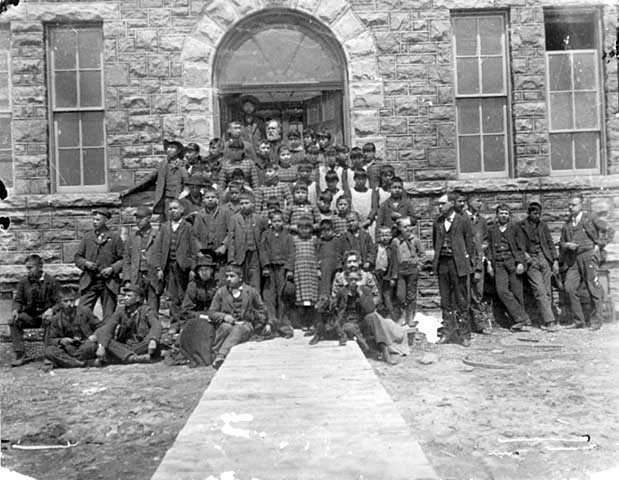

To date, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) has identified 367 boarding schools in the U.S. As an intern at NABS, my principal task has been to research and to compose a historical narrative about each of these schools, documenting as much basic information as possible, such as when the school was built; how many years it was in operation; what religious, governmental, or tribal organizations operated it; which tribes had students taken there; what buildings are still standing; and whether or not the school had a cemetery. In addition to this type of descriptive research, I have also been searching for the location of student records, which might be held by religious organizations’ archives, university libraries, or the National Archives and Records Administration.

This comprehensive list and wide-ranging research are profound due to their unprecedented scope and range. Prior to NABS, this level of inquiry had never been attempted. My efforts here are exciting because I have the opportunity to contribute to this extraordinary work, refining and expanding the knowledge and history associated with each school. Additionally, the information I am collecting will be included in the National Indian Boarding School Digital Archive (NIBSDA) that NABS is developing. By digitizing paper records from boarding schools, NIBSDA will make those files accessible to survivors and their descendants, regardless of their proximity to physical archives.

I am also humbled to help lay a foundation for future researchers. The data we are compiling at NABS today will assist those conducting in-depth research tomorrow. It will be invaluable, for example, for anyone looking for information about relatives who attended a boarding school. They will have ready access to key information and artifacts, such as the location of student records, letters to and from school children, report cards, attendance records, and the GPS coordinates of buildings.

This is my second internship with NABS. During the spring semester of 2019, I interned here to satisfy one of three internship requirements for my master’s degree at the University of Minnesota. That experience was my first time formally working with a Native American organization, and I was eager to begin serving in Indian Country. At that time, I worked on the same project that I am currently engaged in. Little did I know I was laying the groundwork for my future research at NABS over a year later!

This is my second internship with NABS. During the spring semester of 2019, I interned here to satisfy one of three internship requirements for my master’s degree at the University of Minnesota. That experience was my first time formally working with a Native American organization, and I was eager to begin serving in Indian Country. At that time, I worked on the same project that I am currently engaged in. Little did I know I was laying the groundwork for my future research at NABS over a year later!

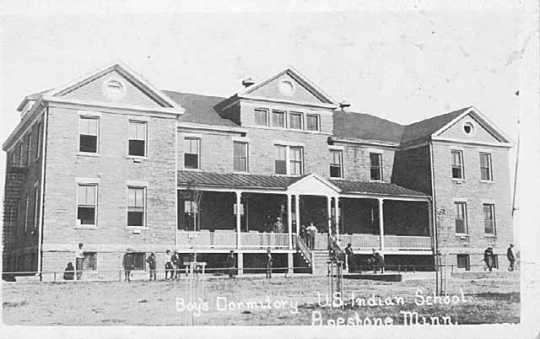

This past spring, I graduated with a master’s degree in heritage studies and public history, a program that focuses on creating equity in cultural institutions and fostering ethical community collaboration. All class projects for this program were completed with real communities to address their unique challenges and goals. One such assignment requiring community-driven collaboration turned into the capstone project for my master’s degree. It started as a discussion with my fellow cohort and Upper Sioux Community member Tianna Odegard. Together, we set up a meeting between NABS and the Upper Sioux Board of Trustees to discuss potential directions for a collaboration. The board indicated the importance of education and healing with regard to Upper Sioux boarding school survivors and their descendants. The result was an important collaborative venture called “Sharing the Records of the Pipestone Indian Boarding School with Its Survivors and Their Descendants,” a grant-funded project through the Minnesota Humanities Center. Additionally, this project documented the partnership process and created guidelines for ethical and reciprocal community collaboration.

Over the past few years of my involvement with NABS, I have been excited to see the growth of vital research, projects, and healing programs benefitting Indian Country, and I am thrilled to continue building my relationship with this impactful organization.

Ellie HeatonResearch Intern